Bespoke Bookplates

Personalized bookplates by Nancy Nikko

A personalized library...

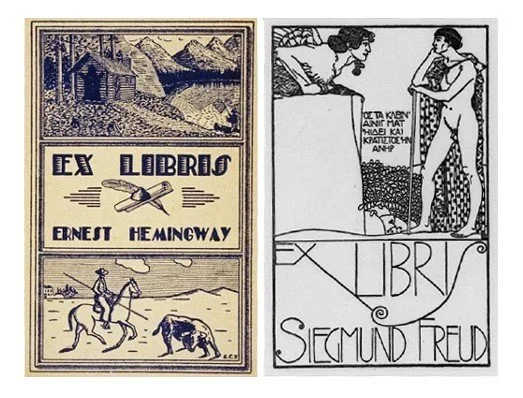

Bookplates have been around for centuries. In the Middle Ages books were prized and having an identifying symbol inside the cover was desired in the event the book was borrowed, forgotten, lost or stolen. As time marched on, bookplates became exquisitely engraved and personalized, often with heraldic imagery.

Today you may not want to put a bookplate in a very rare book, as it could then be considered altered. However, if you collect books simply for the love of them, or to pass down to family or friends, bookplates add a completely different kind of value.

When I come across a second-hand book with a plate in it, I find it far more interesting than a book without. I wonder about the previous owner. Where did this book sit before its present placement? Was it in the collection of a writer? An artist? Did it at one time reside in a1940s studio apartment in the middle of Manhattan? Or a cabin deep in the Appalachian Mountains? Maybe it was in the same house, in the same spot for fifty years – or longer. I must say, if I were a book, I would find it quite shocking to be uprooted after half a century.

Unless it’s brand new, every book has a story outside of its actual story.

Nancy Nikko bookplates, above.

Sometimes there’s an inscription in the front pages. I consider this a bonus and another link to the book’s past. It’s sad that more people don’t include this extra attention when gift giving, and here’s an example of why…

About a year ago I came across a book that dropped behind our sofa - who knows how long it had been there. It was a French cookbook from the 1970s, and I had completely forgotten where it came from, and if I’m honest, I didn’t even recognize the cover. However, I did know it was mine since my husband doesn’t touch a cookbook, let alone one with titles en francais. And since he’s the only other one living here – aside from our Dachshund, who prefers German cuisine - it obviously belonged to me.

I opened it up, and inside was a note from my mother:

Nancy,

Saw this at a Book Sale + thought it looked pretty authentic.

“Love” M

It’s a simple inscription, no more than a sentence really, and typical of my mom’s abbreviated style. Why the “love” is in quote marks I don’t know, but more to the point, it was a voice from the past. My mother died a few years ago, from a very fast-acting brain tumor, the kind that robs you of a proper good-bye. So, when I saw this message, with her distinctive printing – it was an emotional experience. I placed my bookplate next to her note, and someday, when the book is no longer mine, I hope the new owner welcomes this bit of history – along with the recipe for Côte du boeuf à la Bordelaise, which is really quite good.

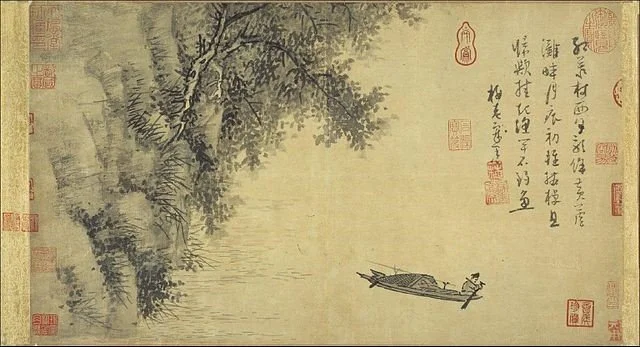

Wu Zhen Fisherman with red chop marks and seals, ca.1350, Metropolitan Museum of Art

In a way, this recording of a book’s lineage reminds me of ancient Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy. It was once the practice, and still is in some cases, for the artist to stamp a finished piece with his chop mark or seal (see image above), as did all the people who owned it thereafter. This resulted in some artworks having as many as 20 marks. In most cases, it not only increased the value of the piece because of the historical record, but also added to the overall aesthetic since most chops are in the same color range (reddish) and are little bits of art mastery on their own.

I’ve never seen a book with multiple plates in this kind of quantity, but perhaps I should start making small Ex Libris chop marks just for this purpose! Like the bookplate, the seal is declaring ownership, by saying ‘The Seal of” such-and-such a person.

Earlier I noted that placing a bookplate in a rare book can decrease its future sale price, but that doesn’t mean that books from the past are always less desirable if they contain one. In fact, they can be invaluable to Antiquarians who are looking to verify provenance, or where the book originated, and in whose possession it has been. That’s important to a collector. And though my personal bookplate may not add monetary value to a book today, were I ever to became a famous author, along the lines of say, Shakespeare or Jane Austen, you can bet that little cookbook would be worth a whole lot more if it had my bookplate in it and was double authenticated by my mother’s handwriting (not to mention the rating note I included of the aforementioned boeuf recipe).

Like the Chinese chop seal, cancelled stamps are something else I admire, and I can appreciate the qualities bookplates share with their postal counterparts - and by that, I don’t mean their mostly rectangular shape. Like bookplates to pages, stamps are put on envelopes at a certain time and place. And like stamps, bookplates travel. I have books with plates from half way around the world and others as close as Minnesota.

The late adventuress, Osa Johnson, was famous in the 40s for writing two books – I Married Adventure and Four Years in Paradise. Both chronicled time spent in Africa with her husband Martin and they became well known for writing about and filming places that few Americans had ever seen.

The Johnsons had a lifetime of adventures that began when Martin was a crew member aboard Jack London’s ship the Snark. There’s much to know about them, but I’ll stick to books and bookplates.

Osa Johnson books

Osa Johnson’s two best-selling books are distinct because one is covered in a giraffe print and the other in a zebra print, making them a handsome duo, and this was my initial attraction to them before I purchased them. I was subsequently surprised when I found that both contained inscriptions, and Four Years in Paradise also included a much-yellowed newspaper clipping from 1953 with the author’s obituary, along with a bookplate. Bobby Gump was the owner, as proclaimed by the illustrated plate of a castle, and underneath his name was a five-digit phone number – and further, a note from his parents:

To Bobby on his thirteenth Birthday From Daddy & Mother 1/24/42.

Even better, this first edition was signed by Osa Johnson herself. Obviously, the news clipping was added later... but how much this tells about the book’s past! And for me, it adds another layer to an already intriguing story.

In closing, while bookplates may not be as popular, or as known, as they once were, I find myself ever more enchanted by these small pieces of art and art history. Perhaps, like those in the late 19th to early 20th century, there will come a time when people begin collecting and trading bookplates again, as the age of the e-book continues and grows, and physical books once again become more scarce.

One of the first bookplates, wood-cut, hand-painted from 1480. These were pasted in the books of the Carthusian monastery of Buxheim by Brother Hildebrand Brandenburg.

The History of the Bookplate

Bookplates as we know them came into being in 15th century Germany. Previously, books were rare and very costly. Before moveable type, books were hand-copied in calligraphy, mostly by monks, and many included illuminations, those beautiful gilded and painted pages that took hours, days and even months to prepare. It’s said that in some monastery libraries, books were chained so they wouldn’t fall victim to a medieval ‘five-finger discount.’

Once the printing press was invented, books were more accessible, though it was still primarily the wealthy collecting them as there was more literacy in the upper echelons, and price remained a factor. But with more books, a place to store them was needed, and aristocrats created fabulous homes with great libraries. Inside their books, they placed their newly commissioned bookplates.

The first bookplates were printed via woodblock and usually included a crest, or coat of arms.

The great German Renaissance printmaker Albrecht Düre designed bookplates for his equally well-known contemporaries, Hans Holbein, the younger, who was Henry VIII’s favorite portraitist, and Lucas Cranach the Elder.

In the early 16th century copperplate plate engraving came into fashion. This, and other methods of steel-plate etching and engraving are called intaglio printing, and it allows for exacting detail compared to xylography (wood-cut), which is not as precise but has its own look and charm.

It’s interesting to note that the use of bookplates began at different times in different places. For example, in France, they weren’t used until the 17th century. Previous to that, French books were most often stamped in gold or blind-embossed with their personal emblem or monogram on the front cover. This is called supralibros.

Queen Victoria’s bookplate for the Windsor Castle Library

Although most European bookplates began with armorial design, in the US the art of the bookplate expanded because most Americans didn’t have a coat of arms or heraldic devices from which to have plates made. Without this fallback, designers instead came up with a motif that fell in line with their client’s hobbies or interests – a quill, dogs, painting palette, religious themes, or romantic classic icons such as castles, landmark trees, and the ubiquitous cat (still popular today). Aside from just a name and decoration, bookplates often had the bearer’s city or favorite saying or motto on it. Or they had a crest made for them to echo the regal European plates.

Paul Revere plates courtesy of The American Antiquarian Society

Some silversmiths were also in the bookplate business because of the materials they worked with, and one of the more famous bookplate makers was Paul Revere. Just like the monks who illuminated pages using pattern books for quick drawing reference, Paul Revere had a number of bookplate frames which he would use for his base, and then he would change out the personal details - crest, mottos, names etc. Revere’s bookplates were done in the ‘Chippendale’ style with intricate flourishes, scrolling and framework. Sometimes just the name and a motto appeared without the traditional Ex Libris we’re more familiar with today. Incidentally, Paul Revere’s shop also printed business cards, cartoons and trade bills….and as if that wasn’t enough, he sidelined as a dentist.

Back to bookplates.

Towards the end of the 19th century, designs began reflecting the art of the times. There’s a myriad of Art Nouveau examples, and this reflects the heightened interest in bookplates, and the collections that were started by newly formed art societies.

In the beginning of the 20th century, when middle-class Americans began to expand their personal libraries, the idea of a bookplate was appealing, but the cost of having one made was prohibitive. Hence the universal bookplate originated, with its blank spot to fill-in one’s name. These can still be found in stationery shops.

The demand for bookplates declined with the increasing popularity of mass-market paperbacks. These books were cheap, and if one was lent to a friend and forgotten, it wasn’t the end of the world. Bookplates were no longer needed as a reminder to return. To put into perspective, according to Mental Floss magazine, in 1939, when the US had an unemployment rate of 20 percent, a gallon of gas would set you back 10 cents. A movie ticket, 20 cents. By comparison, The Grapes of Wrath by Steinbeck, was $2.75. That’s expensive. Then along came the paperback…for a mere 25 cents. By the 1950s, the sale of bookplates diminished by 90 percent.

Today, when I mention bookplates, only about 10 percent of folks know what they are. I guess this follows with the 90 percent drop in sales from almost 70 years ago. And if I mention a bookplate to someone under thirty, the understanding of the word drops to about 2 percent. That’s unfortunate, but like anything that has artistic and/or historical merit, there are collectors and appreciators, and even if far and few between, when you include the whole world, there’s more than enough to keep the art of the bookplate in circulation.

The personalized bookplates I sell can be found HERE.